Do Cyborgs Have Politics?

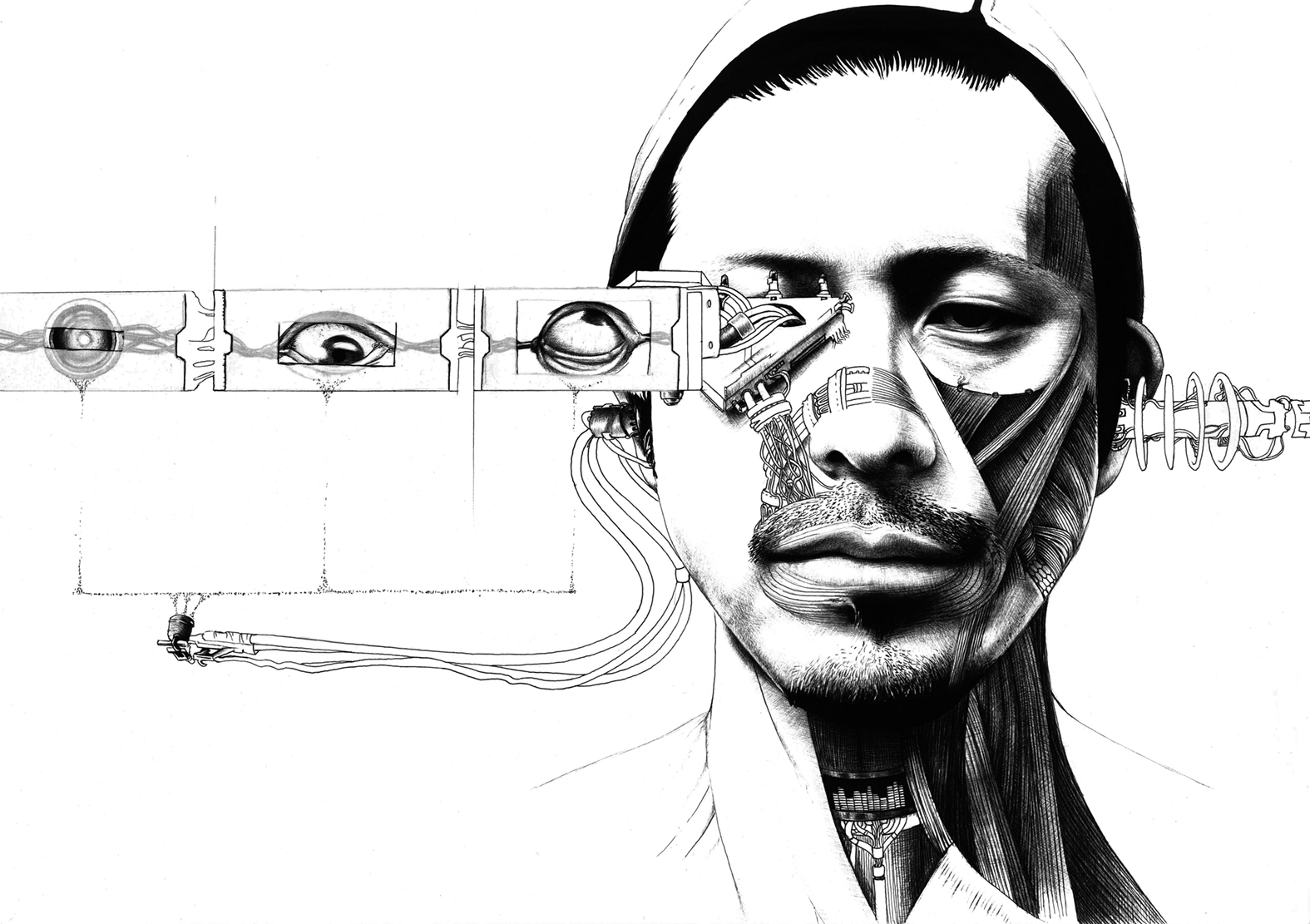

Image by Jamy van Zyl

In 1986, Science and Technology Studies scholar Langdon Winner launched a debate about the power of technologies to shape human politics when he asked “do artefacts have politics?” A technology like the Robert Moses-designed overpasses that arc above the roads from New York City to Long Island, Winner observed, most obviously expressed the 1950s American obsession with car culture in material form. Scratch the surface, however, and the racial politics of these objects becomes clear. By building overpasses low to be aesthetically pleasing to the solo driver or the landscape observer, public transit busses were excluded from traversing these roads. Public busses often serve individuals who do not have enough money to purchase their own cars. Given the racially segregated labor market of the time, fewer people of color had access to the kind of wealth needed to purchase a car.

So seemingly innocent, merely functional highway overpasses helped the beaches of Long Island develop as white spaces, embodying the racial politics of wealth shaped by centuries of slavery and legal oppression, reinforcing segregationist housing policies like redlining which excluded black and brown Americans from certain towns and neighborhoods, and contributing to the current, explosively racialized political culture of the region.

__________________________________

This question of the politics of technological artifacts has perhaps never been more salient than now, when we walk around with computing technologies on our person at all times. Chief among these are the politics of becoming cyborg.

“Cyborg” is a portmanteau of two words whose current meanings were birthed in modern scientific laboratories – cybernetic and organism. The word emerged from the Cold War laboratories of Manfed Clynes and Nathan S. Kline to denote the fusion-by-analogy of biology and technology. Their experiments in the early 1960s tried to replicate biological processes in mice using implanted, non-organic devices. While the technologies worked for certain functions in mouse models, they never reached their ultimate goal: to reconfigure the human body to survive in space.

The technologies of Clynes and Kline followed the principles of cybernetics, a WWII-era philosophy that posited that hierarchical, coded systems of command, control, and communication governed everything from the functioning of cells, to the aiming of weapons, to the structure of human and animal societies. Cybernetic scientists hoped that with the right kind of code and control systems, communication between organism and machine could become seamless, and machines could be made to do biology as good as, or even better than, natural bodies could.

Feminist technology theorist Donna Haraway argued for using cyborgs as a resource for rethinking politics in her 1981 essay, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century”. For Haraway, the cyborg’s politics are based upon dismantling the mythical origin stories we tell about ourselves, our societies, our technologies, and the divisions we draw amongst us along the lines of race, class, and gender, and between colonized and colonizer, laborer and elite. By changing how we tell these stories – including amplifying the voices and stories of women and people of color in particular – she saw new possibilities for freedom and justice. Haraway’s cyborg politics was also a politics that incorporated cutting-edge technologies as part of the liberatory apparatus, rather than blaming technology for all of society’s defects or unilaterally celebrating technological progress as the solution to our ills. Understanding the power and danger of becoming cyborg means, according to Haraway, learning to tell more equivocal stories about the entanglements between modern technoscience and social life than we may be accustomed to.

Thirty-five years later, real-world questions persist about the politics of human bodies and the apparent compulsion to perfect them using technology. While Western society has long been concerned with the perfection and optimization of human bodies, technologists and physicians now have the ability to permanently modify it with technological devices to create new capacities and to make up for both inborn and acquired deviations from the norm. Yet the ability to expand the capacities of the human body also introduces new ways for individuals and groups to be left out, especially in places like the United States and, much more acutely, the global south, where access to health care is highly unequal.

Haraway’s cyborg politics calls us to attend to the unevenness of who might benefit from new technologies of the body. Who can say whether – or more likely, which – enhancements will become economically valuable as saleable aspects of a person’s identity or labor power? What happens to those without such enhancements, given the highly stratified systems of healthcare access that shape health outcomes across the globe? And what of those with disabilities or conditions who don’t want to “fix” themselves, or whose differences require further decades of research to alter?

__________________________________

Medical cyborgs provide one way to think through some of these concerns. Technologies like pacemakers are hailed in the popular consciousness as evidence of good, uncomplicated technological progress. Pacemakers are implanted into people with failing hearts to keep the heart beating in a steady rhythm. The device is tuned through a computer by doctors or technicians after implantation to detect unwanted variations in the heart’s rhythm. The user herself has some input in this process, though the medical expert has the final say in choosing the device settings. When the heart’s rhythm varies too much, the implanted machine detects the aberration and delivers an electric shock to get the heart back into a “normal” rhythm. The thinking is that these devices can fend off unwanted heart attacks, extending life by months or years. This would seem to be an unequivocal win for technology – an example of responsible cyborg-making. After all, what could be less political than saving lives using medical technologies?

But this view of the pacemaker as progress can only be maintained when the popular story of pacemakers leaves out crucial narratives, as scholars Nelly Oudshoorn and Sharon Kaufman make clear. The story of their unlimited promise sidelines patients’ painful experiences: they are painful to have inserted, and they cause pain when they shock the heart back into rhythm. This pain, like many side effects of biomedicine, is often downplayed in favor of emphasizing the benefit of extended life. At stake in such patient stories are questions about who controls how we experience our bodies and which of these stories are deemed important.

Pacemakers also intervene on the family dynamics and cultural politics that surround the late stages of the life course. By preventing death, they extend one’s life beyond that of one’s partner, friends, and kin. Having one implanted might strain one’s finances, causing greater reliance on kin, raising the price of private insurance for everyone enrolled, and draining state public health insurance funds. Living with a pacemaker might strain family relationships if one becomes more dependent in extreme old age or in new forms of debility resulting from the activity of the device, just when they are considered to be of the highest importance. And since they prevent the heart from stopping, a patient must make a decision to turn them off when they are ready to die – potentially sparking more family strife or a crisis of religious conscience – or have the device turned off in the hospital in the moments before death. No one wants to die in a hospital, but pacemakers can make such a death necessary.

The politics of a medical device like the pacemaker, then, is a politics of many dimensions of human life in our modern age: a struggle between patients and professionals over control of the body, the meaning of death, the micro-politics of the family, and the political economy of healthcare. This is a cyborg politics insofar as it is a politics that results from the construction of human bodies as cyborgs – as cybernetic organisms, with key functions supplemented by technology. The material and social consequences of life as a cyborg are many, worthy of celebration and harmful in unacknowledged ways at the same time.

__________________________________

The story of cyborgs in our time also offers room for self-invention and new political sensibilities uniquely suited to our anthropocene age. Self-described sensory cyborgs – chief among them Neil Harbisson and Moon Ribas of the Cyborg Foundation – are well known for advancing the legal rights and creative possibilities of cyborg being. Harbisson and Ribas seek to expand their bodily “sensoriums” by implanting cybernetic technologies that afford them new senses, experiences unknown to other humans. Harbisson has the ability to “see” light beyond the visible human spectrum with the help of a specialized camera that relays information about light wavelengths as vibrations to his skull. Ribas can “feel” seismic activities using an implant that translates real-time USGS data about global earthquakes, accessed via cellular networks, into small vibrations in her arm.

With an expanded ability to sense more of the light spectrum and the very movement of the earth, these exemplary sensory cyborgs describe their bodily experiences as being more connected to the planet. By experiencing the world in new ways, they also describing having an intensified sense of empathy with non-human organisms. New senses they have in the works will be modeled on animal senses, such as the ability to detect true north. By fostering a sense of kinship with non-humans, sensory cyborg technologies could open the way to a new environmental politics fit for the more-than-human ethical frame demanded by life in the anthropocene.

But this could easily be an exclusionary new reality as well, with different classes of people able to inhabit different political possibilities and social roles. Harbisson and Ribas claim that they don’t compare themselves with other humans but with other species. Sensory enhancement is, to them, an individual’s choice. That’s good from the perspective of a liberal democratic politics that imagines absolutely free, fully-informed, choice-making individuals as the basic unit of all politics. But it misses the point that the conditions of production of their new senses is, in practice, only accessible to a small slice of the global elite. Given the challenges posed by providing even basic health care like polio vaccinations and clean water to everyone on the planet, it is hard to imagine a world in which everyone is fully free to “choose” to become a cyborg.

To date, their enhancements have been rejected by health insurance schemes and most of the world’s medical establishment as unnecessary and unallowable modifications. Their operations have been self-funded and carried out off the licit medical grid. These forms of access to bodily care are not available to the vast majority of humans in the world; rather, they reinforce differential, historically patterned access to healthcare resources. One waits with bated breath to see if Harbisson and Ribas can carve out space in existing political frameworks for such interventions to become normal, licit, subsidized, and thus truly a “choice” – or if sensory expansion remains a pursuit of the ambitious and quirky among the global privileged classes that further cements their status as privileged bodies capable of privileged forms of labor.

__________________________________

The politics of cyborgs are the politics of humans. These politics revolve around questions of belonging and difference, production and consumption, waste and renewal, inclusion and exclusion. The politics of cyborgs are also the politics of the planet, and of our non-human planetary companions. They will benefit from an expanded sense of empathy, but they will be harmed by an acceleration of the production of toxic waste from discarded implants. There is no fundamental break between the politics of cyborgs, the politics of humans, and the politics of non-humans, because the complex stories that need to be told about cyborgs involve participants from all three domains. And if, as some contend, cyborgs are the next evolutionary step for Homo sapiens sapiens, then their ethics and history will necessarily encompasses that of the humans which will have given rise to them.

One cruicial thing that Haraway’s cyborg politics and real-world cyborgs demand is a rethinking of the cause-and-effect implicit in Winner’s argument about the politics of artefacts. Rather than let technologies define us, Haraway encourages us to rewrite the scripts we use to describe their genealogy and to meddle with their development.

In other words, how do users of developing technologies shape their politics by actively intervening upon their uses and cultural meanings? This is undoubtedly what sensory cyborgs are already engaged in today by speaking and advocating for their cause, and what patients already do when they make requests about tuning and turning off their pacemakers. But what Haraway envisions goes beyond a Silicon Valley-esque philosophy of participatory capitalism. It is more difficult than simply including people from a wider variety of ethnic, gender, age, sexuality, and class backgrounds to make products for profit. It requires changing what stories we tell about technologies because these stories provide templates for how we interact with them. It means fewer heroes and more collaboration, fewer defenses of the status quo and more stories from those who have been marginalized, believing less in the idea that technologies develop unstoppably and noticing the ways in which technologies as products of social life, which is itself always subtly changing.

If we – the populace, the medicated, the governed – are to have power over the future of our embodied, cyborg lives, we should attend to the points at which we can intervene. We should attend to the stories we tell each other about cyborgs and about new medical technologies. We should attend to who tells them, how they inform science and healthcare policy, and how they integrate with or challenge existing legal, financial, and regulatory structures.

We also need to demand action concerning the new exclusions novel cyborg technologies might produce and what it takes to design them inclusively from tech boosters and technologists. They must consider what kinds of infrastructural changes we would need to make to anticipate and observe patterns of inclusion and exclusion. They must engage in thoughtful storytelling, policy interventions, and collaboration with related industries to make human society more equal in tandem with making it more cyborg. If cyborg technologies are to truly present new choices and possibilities to individuals, as the vanguard contends, we must also deal with the political conditions that can make these choices truly meaningful and freely made.

Author Bio

Danya Glabau is Core Faculty at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research. She received her PhD in Science and Technology Studies (STS) and a B.A. in Biological Sciences from Cornell University. Her work blends STS and Medical Anthropology to investigate how morality, political economy, and patient experience influences what counts as “good” health care in the United States. Her dissertation and first book project examines these issues in the context of the politics of food allergy in the United States. She is now pursuing new research on the financialization of biomedical research and how feminism is shaping the development of virtual reality technologies. You can follow her on Twitter @allergyPhD

Further Reading

Haraway, Donna. 1991. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” In Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 149–182. New York: Routledge.

Kaufman, Sharon R., Paul S. Mueller, Abigale L. Ottenberg, and Barbara a. Koenig. 2011. “Ironic Technology: Old Age and the Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator in US Health Care.” Social Science and Medicine 72 (1): 6–14. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.052.

Kaufman, Sharon. 2015. Ordinary Medicine: Extraordinary Treatments, Longer Lives, and Where to Draw the Line. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Kunzru, Hari. “You Are Cyborg.” Wired 1 February 1997. https://www.wired.com/1997/02/ffharaway/

Oudshoorn, Nelly. 2015. “Sustaining Cyborgs: Sensing and Tuning Agencies of Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators.” Social Studies of Science. doi:10.1177/0306312714557377.

Winner, Langdon. 1986. “Do Artefacts Have Politics?” In The Whale and the Reactor: A Search for Limits in an Age of High Technology, 19–39. University Of Chicago Press.