Transmedia: Art Forms Created in Real Time

A one-platform Immerse response by someone who’s been on them all.

By Caitlin Burns

This piece was first posted in Immerse an initiative of Tribeca Film Institute, MIT Open DocLab and The Fledgling Fund. Learn more about our vision for the project here.

Andrea Phillips answered the question What’s Happened to Transmedia? recently, and having been in the middle of it all, I’ve been chewing on that ever since. I don’t disagree with any of her points, but even though I was deeply involved in the moment Andrea describes, I’ve never actually commented on how I viewed that moment publicly.

As a transmedia producer, I’ve worked on projects large and small, weird and traditional. I was there too, I am here now, I’m still credited as transmedia producer and I still teach transmedia techniques to creators and professionals focusing on art as well as sustainable business models.

One of the reasons I was drawn to transmedia storytelling was a desire to reflect the complexity of the world in the ways we communicate about the world—transmedia was a fascinating way to evolve these concepts, an artistic movement and community, a great leap forward in the discussion of business models commercially, and a community of critique I hope to see again.

Being involved in transmedia meant experimenting with new platforms for narratives, while also developing the language for their critique — both in real time.

Transmedia was both a community and a term-of-art

Much of the conversation around transmedia — like what happened to it — has to do with your perspective on the entertainment industry, creative inclinations, and opinions about the nature of art.

“What was transmedia?” has to be answered before you figure out what happened to it.

Many saw transmedia as a scene — a group of people doing a specific sort of work together. Now, this is not wrong. The group of people most connected to the public conversation around transmedia in the early 2000s included Steve Peters, Brian Clark, Andrea Phillips, Brian Clark, Lance Weiler, Christy Dena, Jay Bushman, Ivan Askwith, Alison Norrington, Jeff Gomez, Henry Jenkins and dozens of others, all working on fiction projects that crossed platforms. Projects like The Blair Witch Project, Year Zero, The Lizzie Bennet Diaries– could all be reasonably called transmedia even though they’re wildly different in structure, content and scope.

Others, such like Jeff Gomez and well, me, at Starlight Runner Entertainment used those same techniques to craft vast, decades-spanning commercial franchises that were also called transmedia. Some voices in advertising included Campfire, Micki Boas, and Jonathan Mildenhall — who pioneered the concept of “Liquid Content” at the Coca-Cola Company, applying transmedia techniques to advertising and promotional efforts around the globe following the successful transmedia campaign for The Happiness Factory.

Lina Srivastava, Katie Elmore Mota and Harold Moss were using these techniques to educate, engage and inspire people about important real-world issues. Projects like Who is Dayani Crystal?, Priya’s Shakti and East Los High are going strong and helping influence and educate.

Still others such as Henry Jenkins, Janet Murray and Frank Rose were all examining the impact and cultural significance of everyone’s work as it happened.

Applying the lessons of those productions has changed communications, technology, media and the way we talk about financially successful entertainment projects.

Beyond that core group of creative practitioners, transmedia storytelling as a concept connected people all over the world (U.S., Canada, Australia, Colombia, Europe, Asia, Brazil, etc.) in an incredibly short time period to create new work, attempt to create a new industry vertical and share insights about this new communications paradigm. This wider group of transmedia creators included dozens to hundreds of people all exploring the idea at the same time.

By the techniques’ very nature, these creators were online, connected by social media and talking about what they were doing while they were doing it. It was a truly 21st century exploration of an artistic and media technique that was being tested, created and re-evaluated in real time.

While one group may have started that conversation, it’s important to note how quickly that group expanded and bled across practitioners in other industrial categories. While many of the online conversations at this time were about semantics, or who invented what term, or what was or wasn’t “transmedia’” or “‘cross-media” — best practices and techniques did emerge. These mostly included the practice of listening to and evaluating artistic production methodologies by multiple creators simultaneously, including the intended audience of the projects.

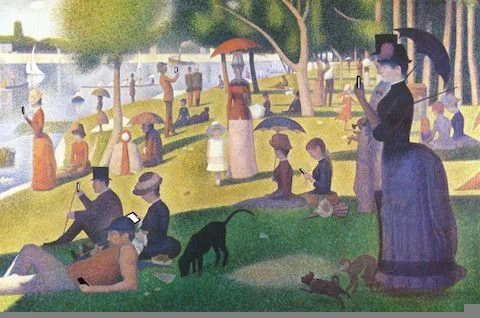

These were the questions that ultimately, people were asking in real time, and the great news is that many, many, many answers emerged. All at once. Often contradicting one another and sometimes with mean hashtags and theatrical fake protests, and a fair smattering of photoshopped homage posts.

Imagine if the Impressionists had Twitter, would Monet still paint the same way? Would he get into flamewars about his daily posts of Rouen Cathedral? Would 1905’s 4chan make mean memes about misandry in Degas Ballerinas? Would Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings better reach his audience as a travel blog? Debussy would definitely have been periscoping his practice sessions — “establishing a new concept of tonality in European music" — such a hipster.

Depending on the creator’s personal interests, transmedia was all about audience building, or all about creating decade-spanning franchises, or only about creating online narratives on dozens of purely digital platforms. It was all of these things and none of them.

The reason transmedia could serve as a rallying flag for so many people experimenting in so many different ways was because it was not a production or genre or business in and of itself, but a means to describe all of the above. “Transmedia” has always been a useful term to describe a strategic technique — a term of art and commerce describing a practice of connecting stories and storyworlds across platforms.

Transmedia is the technique, not its results.

Crews, cliques, collaborators and communications

When I was entering the field just out of school, online arguments with people whose work I admired felt like the end of the world –rather than the tone of debate between colleagues that were my expectation of professional life. In some ways, it made the conversation around transmedia especially daunting, in others, it was a necessary part of defining an artistic process. What made this process different is that all of the conversations and the work being developed and critiqued was happening simultaneously.

Especially in artistic fields, if you’re not getting argued with on the internet, your idea probably isn’t that interesting. Not all arguments are good—and this is no excuse to be a jerk—but debating these artistic and structural ideas, challenging their viability and their results is a necessary part of making any truly exciting media.

Being involved in transmedia ten years ago meant experimenting with new platforms for narratives, while also developing the language for their critique—both in real time.

Before I was a transmedia producer, I threw high-concept raves: live events for hundreds or thousands of people mostly around New York City. We’d bring together different groups of artists, musicians, DJs, etc…. Crews of dozens would collaborate to create a theatrical space you could dance in, and use similar creative ways to invite people to those events — physical invitations, emerging social networks, SMS phone trees. You’ll have to trust me though, these happened before high-res cameras were in phones.

These were my first professional producing experiences. When I began working on commercial intellectual properties, it was astonishing to me that the practice of infusing the messages, meaning, aesthetics and storyworld of each production across all the platforms necessary to reach an audience was not a formal part of the production of many major franchises. These had been the only way to get 25 crews of artists, musicians, fire-dancers and techno-futurist-DIY-engineers to get onto the same page.

It seemed so commonsense and obvious that this was the way one had to consider a production for it to be successful. That also means ensuring that all the collaborators you’re working with can commit to this together, while the work is in progress. That means working with people from other specialties and collaborating, and bringing in new groups that can add new levels to each production.

If you’ve ever promoted or even attended music events, you’ve probably experienced someone arguing about what is “real” Punk, “real” Techno, or “real” Dubstep. I felt the same way about the conversations of “real” transmedia applications at the time.

It’s important to have like-minded collaborators and colleagues with whom you can pursue the creative work you want to explore — but it’s also easy to fall into the trap that if someone isn’t doing it the same way you and your group does, it’s not legitimate.

We’re starting to see the same crews and cliques developing in Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality — if you weren’t making cinematic VR before 2015 you’re not in the club. If you hadn’t worked in Unity before 2015 how can you say you’re making a “real” VR game? If you’re only working in monoscopic documentary, are you really making VR? It will be fascinating to see how all of these groups collide in the next few years when VR platforms put them all in direct competition for the same audiences. It will be even more interesting as these distinctions emerge into viable industry categories of their own.

Transmedia never stopped being relevant, the need for the specific term is more niche…

Brian once told me this picture was taken when IBM’s Watson decided to make some robots dance and he was there. Whether it’s true or not, that’s the face I hope we all make when we see the future come to life.

It’s nearly impossible to talk about transmedia without bringing up Brian Clark, who repeatedly told us that Transmedia is a Lie.

He eloquently described the concept of “Buzzword Fatigue” the first time I saw him speak. He had weathered the dawn of “Independent Film” and had seen all of this happen before as terms were imagined, defined, redefined, assimilated and finally, normalized into niche parts of industries.

Transmedia’s greatest prominence was in an incredibly ancient time — 8 years ago — when there were no digital signing systems for contracts, no one had ever heard of Gangnam Style and YouTube couldn’t host videos longer than 10 minutes.

These transmedia conversations happened in the days before digital streaming networks like Netflix, Hulu and Amazon were considered legitimate options for distribution of Hollywood films. The iPhone was 18 months old, the Motorola Droid came out the same month — offering broad multimedia support for Android devices for the first time. This was before people were making millions of dollars per year on Instagram.

The things that people saw potential in, that were just barely reaching audiences then, are now multi-million dollar industrial ecosystems in their own right, and dealing with them no longer seems like the same experimental stretch to commercial interests or artists.

In 2010, Producers’ Guild of America credited Transmedia Producers in 2010 — as those that supervise the development of an intellectual property across 3 or more media platforms. At this time, many productions were still putting promotional images on websites and calling it a day for audience engagement in digital spaces. This was also a time when high level media executives would tell you with a completely straight face that social media like Facebook would be “over” within a year.

“Transmedia” as a term allowed creators to have this conversation from new angles — thinking long-term as well as short term — by providing creatively satisfying results to audiences who could now communicate their responses directly.

While the community of artists and creators who make up Andrea’s definition have moved on to other things, philanthropic and commercial interests have assimilated the techniques into their best practices — the term remains in crediting, job descriptions, educational curricula and philosophical debates about the nature of art.

So, what happened to transmedia?

The most visible use of transmedia is still the work done for high profile entertainment properties.

The Walt Disney Company has embedded Transmedia Producers in all their franchise teams — building on a model of franchise development that has expanded to incredible profit in recent years. Learning from successes like Pirates of the Caribbean, Disney Fairies, Tron Legacy and others, Disney put storyworlds first in its decision making. It’s invested heavily in purchasing or expanding rights in existing story worlds, Pixar’s intellectual properties, Star Wars, the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

It’s impossible to create a sustainable 10-year-plan for a narrative franchise like DC or Marvel’s cinematic universe without a transmedia strategy. Without knowing what characters live or die, how do you know how to engage an actor for a long-term contract? Without a production schedule, how do you engage licensees to create games or book trilogies that will satisfy audiences who have shared 9 films worth of storytelling with their favorite characters? These creative decisions are integral to business decisions and vice versa, and someone has to keep track of it all. Consequently, ensuring that their production team includes people with eyes on the health and well-being of storyworld’s overall development is not just useful, it’s essential.

At the Produced By New York panel The Storytelling Horizon: Digital Possibilities for Producers on October 29, 2016 Meagan Wilson discussed HBO’s strategies. “For Silicon Valley we launched 5 ‘in story’ websites — you can call that promotional but there was never a ‘tune in.’ HBO has embedded transmedia producers on all their original projects and it makes a huge difference… The work is harder without someone embedded in the story and production.”

On that same panel, Transmedia O.G. Mike Monello (Campfire, The Blair Witch Project) talked about his experiences in advertising “Nobody has ‘digital’ in their title anymore, they’re producers—stop pretending there’s a difference. We have to drop the idea that there’s a difference between a producer, and a producer working on digital platforms,” he said. Blaine Graboyes (GameCo) had introduced the panel by saying “we’re past the day of digital being an appendage of the production. It’s the production.”

This is the biggest change from where we were when transmedia was at its peak as a trend. Everything that people saw as possible — social media adoption, people creating work and sustainable careers on these platforms, digital distribution channels funding award-winning content — are now real, maturing industry categories. Creators can pay their rent by producing for audiences solely on social media platforms. TV shows are distributed direct to audiences via web-browsers. Novels are written by writers’ rooms and distributed to mobile applications weekly.

People simply no longer need a term to describe experimenting with multiple platforms creatively the same way they did 10 years ago.

Many funding bodies around the world, still require transmedia strategies to expand a production across multiple platforms, but that’s part of your business plan now. It’s a given that you need to have a creative marketing and advertising strategy to reach an audience that’s spread throughout the real world and the Internet.

University students study transmedia techniques as part of film, television or communications majors, with the opportunity for graduate studies in transmedia. Look to Ithaca College, Ball State University, MIT and USC as a few examples.

For students about to enter the professional landscape, making a living means getting your work seen, and it’s never been easier to show what you can do. Using these techniques can help you create ambitious work and distribute it publicly, and to demonstrate your competence to future employers and funders.

As for the luminaries of transmedia past, some are still working as transmedia producers for Hollywood, television (or digital ) networks, game publishers, or book publishers. Some are creating magnificent new storyworlds, like Blizzard’s Overwatch or whole new parts of others, like Chuck Wendig’s Star Wars contributions. Others are called “executive producers” or “producers,” or “executive vice president,” and are now more known for work on one platform… that happens to be incredibly robust on half-a-dozen other narrative platforms.

Still other transmedia luminaries like Brian Seth Hurst and Ken Ecklund continue to follow their curiosity about experimental technologies for narrative media, and are helping to communicate the potential of new technologies to the world.

While the number of transmedia conferences and events in North America have dropped off in previous years, high-level seminars and conferences have emerged across Asia as the demand from creative industries grows to meet the needs of billions of fans.

Transmedia isn’t dead. Like all of us, it has matured, to one extent or another.

Transmedia is still a by-word for curious, capable and creative people who want to explore how complex stories and communications can engage people in new ways — and it takes a tremendous amount of skill to create and manage a successful transmedia production.

Transmedia techniques — how you adapt and strategize your production across many platforms to connect to and reach your audience — have never been more critical to creating successful stories for art or profit.

Whether you know that those techniques are called transmedia storytelling isn’t necessary, but it helps.

As for me…

Disney Descendants is an original transmedia franchise launched by Disney Television Group in 2015.

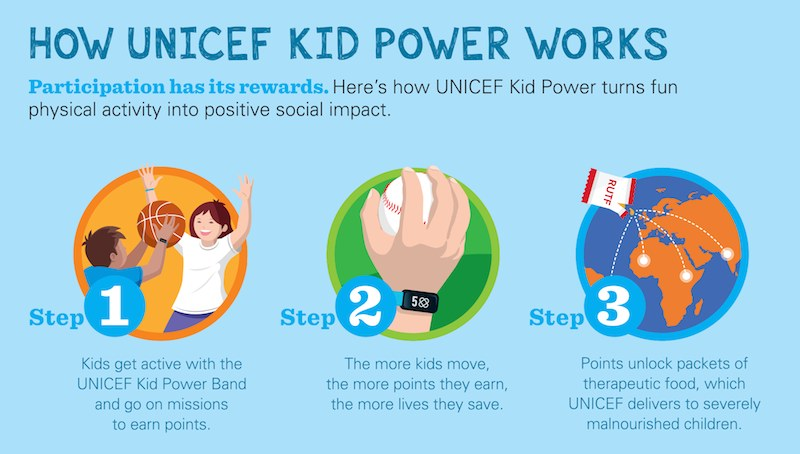

Lately, I’ve worked on a few entertainment franchises, a lot of emerging narrative technologies and I’m working increasingly for groups that aren’t traditionally creating media — like my work with US Fund for UNICEF.

I’m brought in often as a business consultant for media companies that need to understand how to most sustainably implement transmedia techniques with existing transmedia production teams as to create them whole cloth. It’s a big change from when I had to justify the idea that you needed to reach your audience where they lived, or the idea that story expanding to new platforms wasn’t crazy or that multiplatform strategies meant more profit. More people understand that transmedia strategy is required for a successful story business than don’t — the problems are in execution.

I’ve spent time working on the new, new platforms AR & VR, creative producing and now focusing on the study of how to make those new content ecosystems robust and profitable for large corporate and institutional clients.

In September, I launched a monthly publication, Pax Solaria, exploring what humanity will look like in the high-tech future. I plan to live in the future, and would love to hear your thoughts on a future we can live in together.

Want to yell at the author and tell her she’s wrong? (Kindly, Please): Caitlin Burns